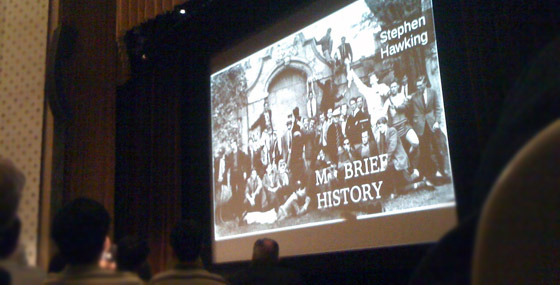

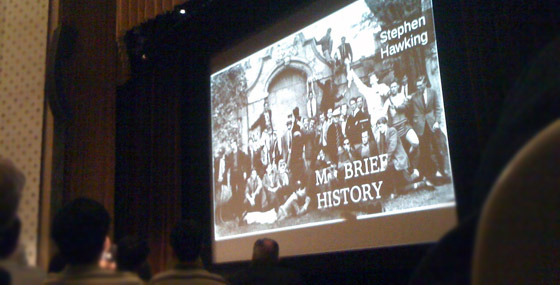

Stephen Hawking lectures on “My Brief History,” packs the house

On Tuesday, January 18, 2011, physicist, cosmologist, writer, and science celebrity Stephen Hawking spoke in Caltech’s Beckman Auditorium on the subject of “My Brief History,” an autobiographical journey through the life of one of the most famous scientists in history.

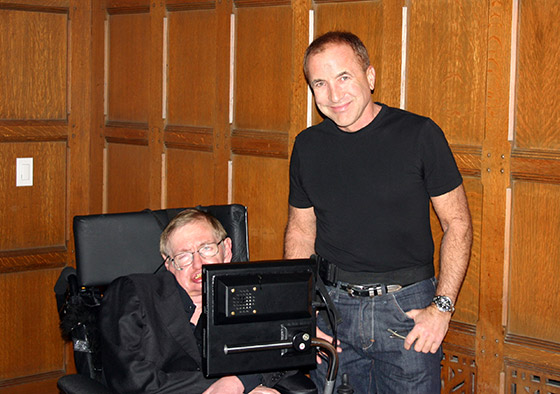

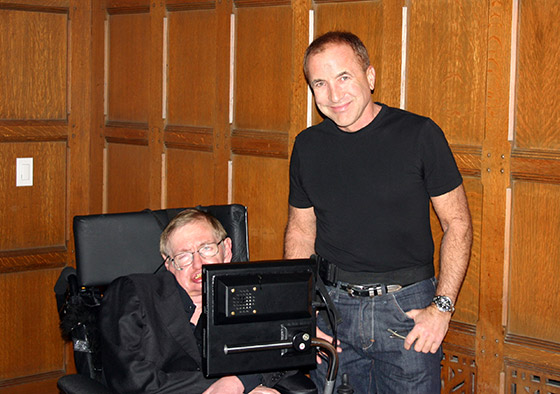

Tickets were in such high demand that I had to go as a member of the press, writing for Scientific American, Skeptic, eSkeptic, and Skeptic.com, and even then it wasn’t clear I was getting in to actually hear the lecture until after the press junket that afforded us a photo opportunity to pose with The Great One (see below).

Despite his handicap that prevents him from moving anything but a tiny cheek muscle, Hawking is fiercely independent and insists on writing his own speeches and delivering them sentence by sentence through a computer cursor command that he controls through twitching that one muscle, the movement of which is picked up by a small camera attached to his eye glasses (see close up photo below).

Propped up in his chair with his computer screen in front of him, Hawking delivers the lines of his speech sentence by sentence, which you can hear being commanded by a barely perceptible short buzzing sound that advances the already-written text line by line.

click image to enlarge

Hawking’s talk was a mix of anecdotes about his parents and upbringing, his schooling and early education, and his science—all of which have been outlined in countless articles, books, films, and biographies—but it was refreshing to hear it directly from the man himself, who rarely addresses the public about personal matters. Hawking was obviously gifted from early childhood, plus had the support of well-educated parents and opportunities for an excellent education. What he lacked, by his own admission, was motivation to achieve. In fact, Hawking noted that the whole point of going through higher education was to show how little effort was needed to succeed, and he took every advantage his genetics gave him for cognitive superiority to cruise through his courses while hardly lifting a finger.

All that changed when he was diagnosed with ALS, which jump-started his ambitions to roll up his sleeves and get to work on something significant to complete his Ph.D. and provide for his new family before…well, before his inevitable demise that is the prognosis of this disease. Four decades on Hawking remains paralyzed but very much alive, living life to the fullest that he can (Caltech cosmologist Kip Thorne, who hosted the event, recounted a trip to Antarctica that Hawking organized, as well as his well-publicized zero-gravity excursion in the “vomit comet” jet that flies through parabolic arcs that enable brief snippets of weightlessness. Apparently Hawking plans to be one of the first tourists into space aboard one of the developing private space flight companies.

Hawking also has a keen sense of humor, although it isn’t clear that if any of his lines were delivered by anyone else that they would be found funny. His situation is so unique, and his mind so interesting, that audiences seem eager to respond to anything he says that isn’t straight reportage about his life or science.

In previous talks that I have attended by Stephen the Q & A inevitably includes a god question, but in those days Hawking took questions from the floor, which took too long to answer so now he fields questions before the talk from Caltech students, who read them aloud to the audience, followed by Hawking’s prepared answer. Here are the three questions and Hawking’s answers:

Student question #1 from Marc Favata, a Caltech postdoc in physics: “As you well know, one of the major research efforts at Caltech concerns the detection of gravitational-radiation with LIGO (the Laser Interferometer Gravitational-wave Observatory). When the upgrades to LIGO are complete in the next 5 years or so, we expect to detect multiple gravitational-wave events from merging neutron stars or black holes. Considering the uncertainties in our understanding of the rates at which these mergers happen, are you optimistic or pessimistic about the prospects for LIGO to detect something? More importantly, could you speculate on what might be some of the ‘big surprises’ that could come from gravitational-wave observations?

Hawking: “There is uncertainty in the rate of black hole or neutron star mergers. But after the upgrade, LIGO should be able to detect gravitational waves from neutron star binaries, and we know they exist. The most exciting result would be to find something we don’t expect. I can’t say what that might be, because then it wouldn’t be a surprise.”

Student question #2 from Shiri (Teresa) Liu, a Caltech physics sophomore: “In one of your TV series, you proved that time travel from the future to the past is impossible by holding a party for time travelers from the future. In your experiment, you planned to hold a party for the time travelers at noon on a specific day. You printed many copies of the invitations and counted on some of them to survive for thousands of years, so that time travelers living in the future will read the letter and use a time machine to come back to your party. However, nobody showed up at noon that day, so you concluded that time travel from the future to the past is impossible. Here is a paradox that I have encountered by changing your party plans: Suppose that time travel from the future to the past is, in fact, possible, and suppose that you have made a firm decision, before the party starts, to print and preserve the invitations forever. Suppose, you hold your party and time travelers do show up; but soon after your party you suddenly change your mind and destroy all the letters. What will happen? Will the time travelers who showed up at your party suddenly disappear into the future when you destroy the letters? If so, haven’t you just changed the future in the past? And, by the way, I’m just curious; do you still have all the invitation letters?

Hawking: “Even if I destroyed all the invitations, the television program is on YouTube, so time travelers from the future, would know about the party. Of course, they would also know that nobody came. Maybe that’s why they didn’t turn up.”

Student question #3, from Sirio Belli, a first-year grad student at Caltech in astrophysics: “The great Russian physicist Lev Landau, in the 1930s, 40s, and 50s, ranked physicists on a logarithmic scale from 0 to 5 according to their productivity. He assigned the best score of 0 to Newton, 0.5 to Einstein, 1 to Paul Dirac and 2 to himself. What do you think would be your place on this scale? Many journalists have called you ‘the new Einstein,’ but I would like to know your opinion about the importance of your contributions to physics.”

Hawking: “Landau was good, but not that good. People who rank themselves are losers.”

A good time was had by all, and by all I mean the 1,100 people inside Beckman Auditorium, the additional 400 people in Remo Hall watching a video feed, and hundreds more on the lawn outside Beckman watching and listening on big screens and speakers. It is both rare and refreshing to see a scientist so popular that people were lined up to nab the handful of seats set aside for the general public as early as noon that day. Such is the nature of celebrity, even science celebrity.